| Home |

| The Cork-Cutter’s Trade |

In England, the cork-cutter’s trade disappeared with the industrial revolution. However, family history research may find cork-cutter ancestors. These notes give a look at their work in bygone times.

A portrayal of the bustle of commercial activity in Georgian London, given in a poem titled London’s Summer Morning, written by Mary Robinson in about 1795, recognized the role of cork-cutters in the excerpted lines: (1)

|

In England, the first cork-cutting workshops started to operate in London at the end of the 17th century. Cork, obtained from the bark of a type of oak tree that flourishes around the Mediterranean and Portuguese coast, was valued for a variety of uses including as a bottle sealer, such as wine corks, and for the inner soles of shoes. The interest in cork-cutting spread and, during the 18th century, workshops were established in many towns throughout Britain (2).

A manual, printed in London in 1753, gave a description of the cork-cutter business:

The Cork he cuts is the bark of a tree we meet with in Spain, and other warm countries; few serve apprentices to this trade; women are chiefly employed in it, and will earn above a shilling a day in cutting them, at so much a dozen.

Fifty pound will set up a Cork-Cutter. (3)

In the above account, there is a distinction between the business manager and the labourers. In family history research, where the identity of cork-cutter is found in trade directories, electoral poll books, wills, and other records, it can be assumed that the person was the proprietor of a cork-cutter enterprise.

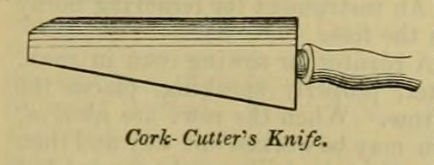

The 1804 publication of The Book of Trades, or Library of the Useful Arts observed that for the cork-cutter’s work ‘the knives used in the operation have a peculiar construction, and they must be exceedingly sharp’ (4). Below is an illustration and description of the cork-cutter’s knife extracted from a nineteenth century reference book.

|

In the above illustration the items hanging from the ceiling are flotation devices or life jackets designed to assist a wearer to keep afloat in water. The text to accompany the illustration described:

The cork waistcoat is composed of four pieces of cork; two for the breasts, and two for the back, each nearly as long as the waistcoat without flaps. The cork is covered, and adapted to fit the body. It is open before, and may be fastened either with strings, or buckles and straps. The waistcoat weighs about twelve ounces, and may be made at the expense of a few shillings.

A report from 1835 stated that imports of cork to England, mainly from Portugal, amounted to about 44,000 lbs. annually. At this time, cork-cutters in England were protected from foreign competition by a duty of 7s. per lb. on manufactured corks (5).

Cork-cutters did not appear to have their own trade association. By comparison, for leather workers, each leathercraft had its own trade guild, such as the saddlers, shoemakers (cordwainers, patten-makers), glove makers etc. (6). Some London cork-cutters became members of one of the City of London Livery Companies. For example, a number of cork-cutters had an association with the Clothworkers’ Company of London (7).

By the end of the nineteenth century, cork products were made using machinery, rather than being entirely hand-crafted. Charles Booth’s study on working-class life in London towards the end of the 19th century, published in his multi-volume book Life and Labour of the People in London, included a description of the working conditions in a cork-cutter’s workshop, which is reproduced in the extract below.

|

| Ladies’ Fashion |

In the eighteenth century fashionable women wore padding, called rumps, under their petticoats to give extra fullness at the back of the dress. These rumps could be made from a variety of materials including cork (8). The print below, designed as a parody, shows a shop making and selling cork rumps; two ladies are trying on the rumps while two women are carving the cork rumps at a desk with the sign "Money for Old Corks". The finished cork rumps, of different sizes, are stacked on shelves behind the lady cork-cutters.

|

|

A Satirical Print, 1777:

"Monsieur le Que Ladies Cork-Cutter from Paris Wholesale, Retail, & for Exportation", The British Museum collection online (museum number J,5.133). |

| Next: | Trade Cards and Bills |

| and | |

| The Magnificent Cork Oak Tree |

Notes

(1)

The poem London’s

Summer Morning  .

.

Biography of Mary Robinson (1757–1800),

Wikipedia  .

.

(2)

An informative review of the cork-cutter profession is given by

Cheryl Bailey, "Bark’s Requiem: the forgotten trade of corkcutting",

Family History Monthly, January 2004,

(3) The General Shop Book: or, The Tradesman’s Universal Director, printed for C. Hitch and L. Hawes in Paternoster Row, London, 1753 (Google eBook).

(4) The Book of Trades, or Library of the Useful Arts, Vol. 1, 1804, London, pp. 144–148.

(5)

"Oak-Bark Peelers", The Penny Magazine, 31 January 1835, p. 37

(Google eBook  ).

).

(6) Review of My Ancestor was a Leather Worker, the Society of Genealogists’ Newsletter, London, April 2021.

(7)

The Records of London’s

Livery Companies  (ROLLCO online database).

(ROLLCO online database).

(8) Kendra Van Cleave,

Late

18th Century Skirt Supports: Bums, Rumps, & Culs  , article online.

, article online.

Text Copyright © WhistlerHistory 2024.